Share on

- by THENATIVEGRAPES

- Filed under 2021, Awards, Books, Friuli Venezia Giulia, HISTORY, MODERN, Native Reds, Pignolo, Senza categoria, Wine.

- Tagged Book, Book review, Pignolo.

Ben Little

Self-published

ISBN 9791220071765

Online orders: THE MORNING CLARET BOOKSHOP

*Republished here with the kind permission of Jancis Robinson.com

Nothing I say can do this book justice. It’s a book like no other book I have reviewed. It’s poetry. It’s a fairground. It’s Alice in Wonderland meets Robert Frost on the road less travelled. It’s Muriel Barbery lost in an amphora, Einstein with anthocyanin-stained hands, a self-help hack, a work of art, a scrap book, a paean, an odyssey, a howl at the universe, a prayer to the moon. It brought me to tears more than once. Several times I had to put it down, stop reading, unnervingly flooded with emotion, grappling with questions that seemed too big for a wine book.

Until now, I’d have thought that you cannot possibly write a whole book about a single grape variety unless it’s something like, say, Chardonnay – made by pretty much everybody who matters or doesn’t matter, planted in pretty much every wine region and made in every style under the sun. But even then, I’m not sure there’d be that much to say.

When Ben Little emailed me out of the blue to say he’d written a book about Pignolo, about which I knew very little except that it’s a grape variety from north-east Italy that very nearly became extinct (Wine Grapes notes that there were but 20 ha (49 acres) in 2000), I was intrigued.

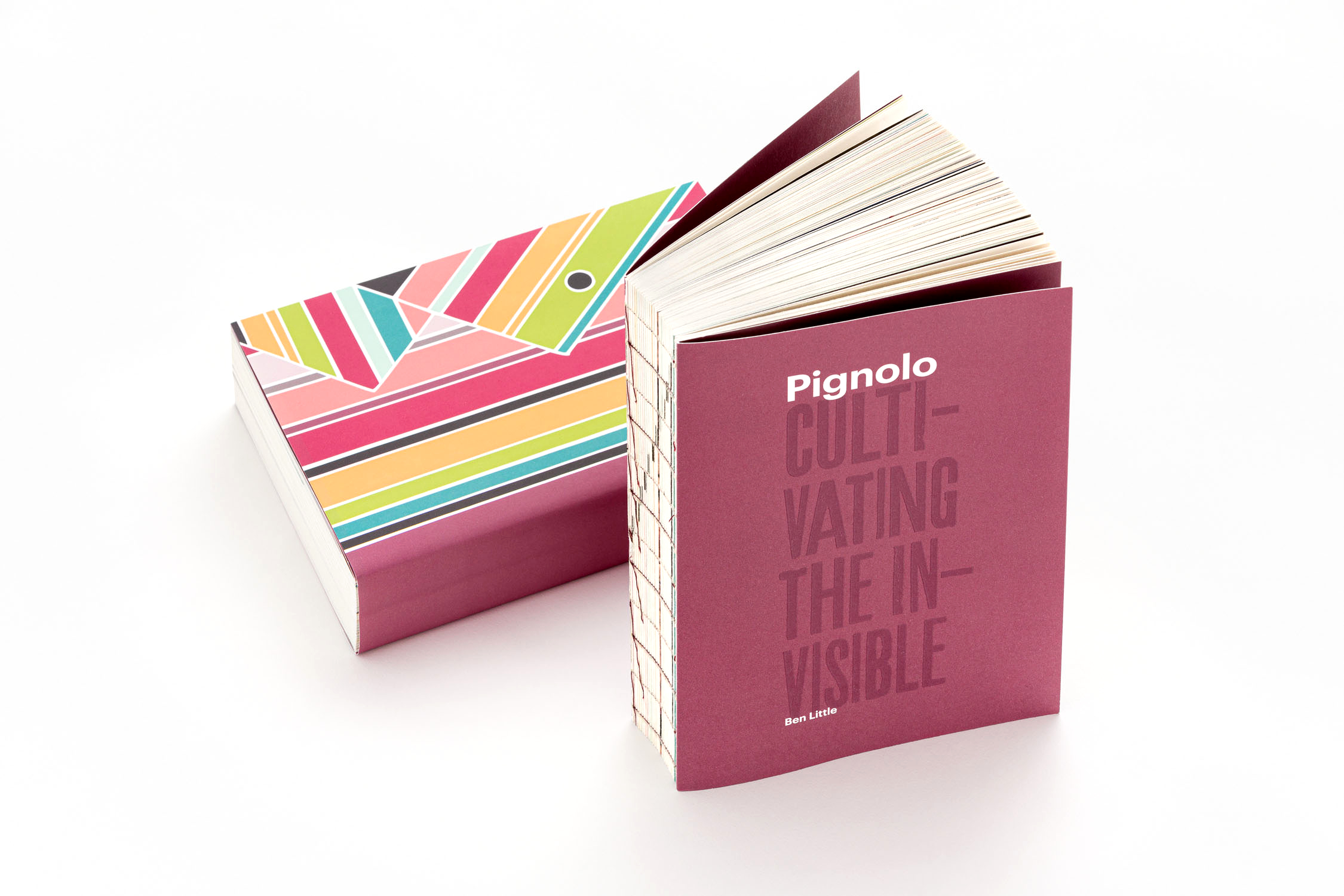

A wildly coloured, hefty stash of pages arrived on my desk a few weeks later with no discernible title on the book jacket. It looked like a gift, begging to be unwrapped, provocatively mysterious. I opened it. Inside, a child’s scribble informed me, after the dedication page, that this book was ‘for all who are waiting in line to be born’. Curious.

The introduction was even more intriguing. Little starts by saying, ‘This is an “animal-trans-plant kingdom” story for the absolute beginner’s mind…’ and goes on to call his book ‘a mixed-media, quasi-technical tale about a black grape, its home, its custodians and its wines’ that for him has ‘necessitated the purging of a lifelong accumulation of informative stuff’. He writes about a ‘truth story’, trying to create universal sense, the conundrums of beginnings, sleep-talking and finding understanding, and then invites us to come ‘kick some leaves’ with him. I was just starting to feel as if I’d landed up at the Mad Hatter’s tea party.

Then I turned the page to find a quote by Friedrich Nietzsche: ‘There is always some madness in love. But there is also some reason in madness.’

Was this book, I wondered, love, reason or madness?

He describes himself as a recovering economist. He’s Irish, married to a Friulian, and he first came to Friuli in 1998 with his (new, Friulian) girlfriend. At a meal with what he didn’t yet know were going to be his in-laws, he was introduced to Refosco. In love, and then, suddenly, in love again, differently, it ignited a passion for indigenous grapes that eventually led to TheNativeGrapes.com and Little moving with his wife and two children from their life in Ireland to settle in Friuli.

Little’s foray into Pignolo, which seemed to be initiated by something of a personal crisis of identity and meaning, began in the spring of 2016. He says that he didn’t know what he was looking for, but he was searching. He didn’t choose Pignolo, he writes, ‘Pignolo had chosen me’. A small project, he thought, after having consulted Google. There were only 15 producers. Only 15 Pignolo winemakers in the world. All on Little’s doorstep, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, where he’d been living for six years.

It turned out that 15 producers were more like 33, and the more Little dug, the more he realised that this grape variety, so very nearly lost to the world, had quiet guardians in the form of stubborn Friulians. He knocked on doors, got people talking, organised tastings, and suddenly there was a tiny revolution, a revival, under way. This is the story.

The first few pages are a weirdly riveting and somewhat bewildering philosophical peregrination through the meaning and power of creativity, art, imagination and understanding. Pignolo is there, on the pages, but really Little is writing about emptying minds, seeking, living by instinct, ‘lighting your inner wilderness’. ‘In a moment of darkness’, he writes, ‘instinct gives you insight. Pignolo is instinct. I listened to its voice.’

It sets the tone for the whole book: a restless, soul-baring, relentless search that weaves weft and warp threads of politics, history, chemistry, geology, geography, biology, oenology, philosophy, culture, ampelography, philology and glossology, angst, existentialism, identity and etymology into a richly embroidered fabric.

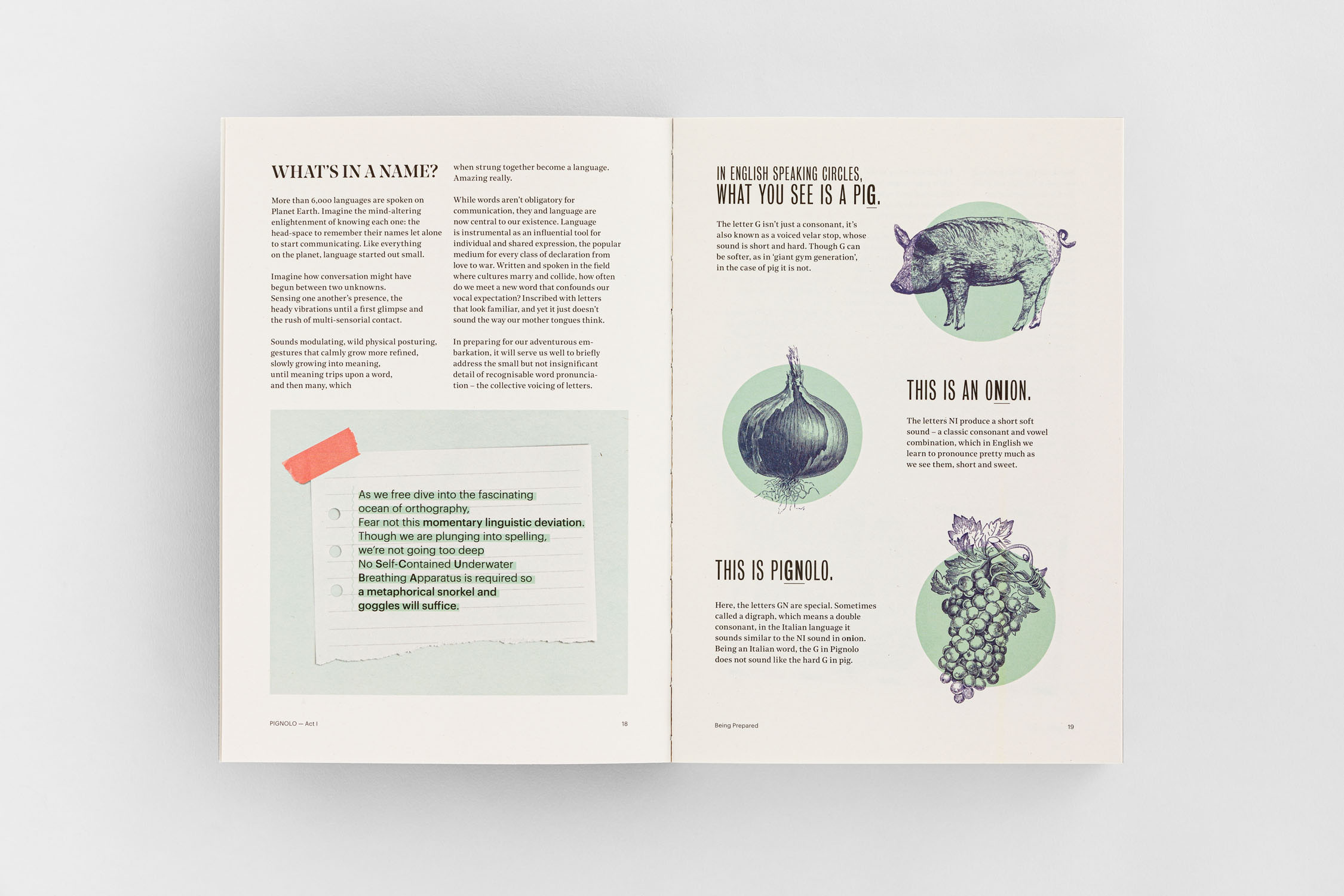

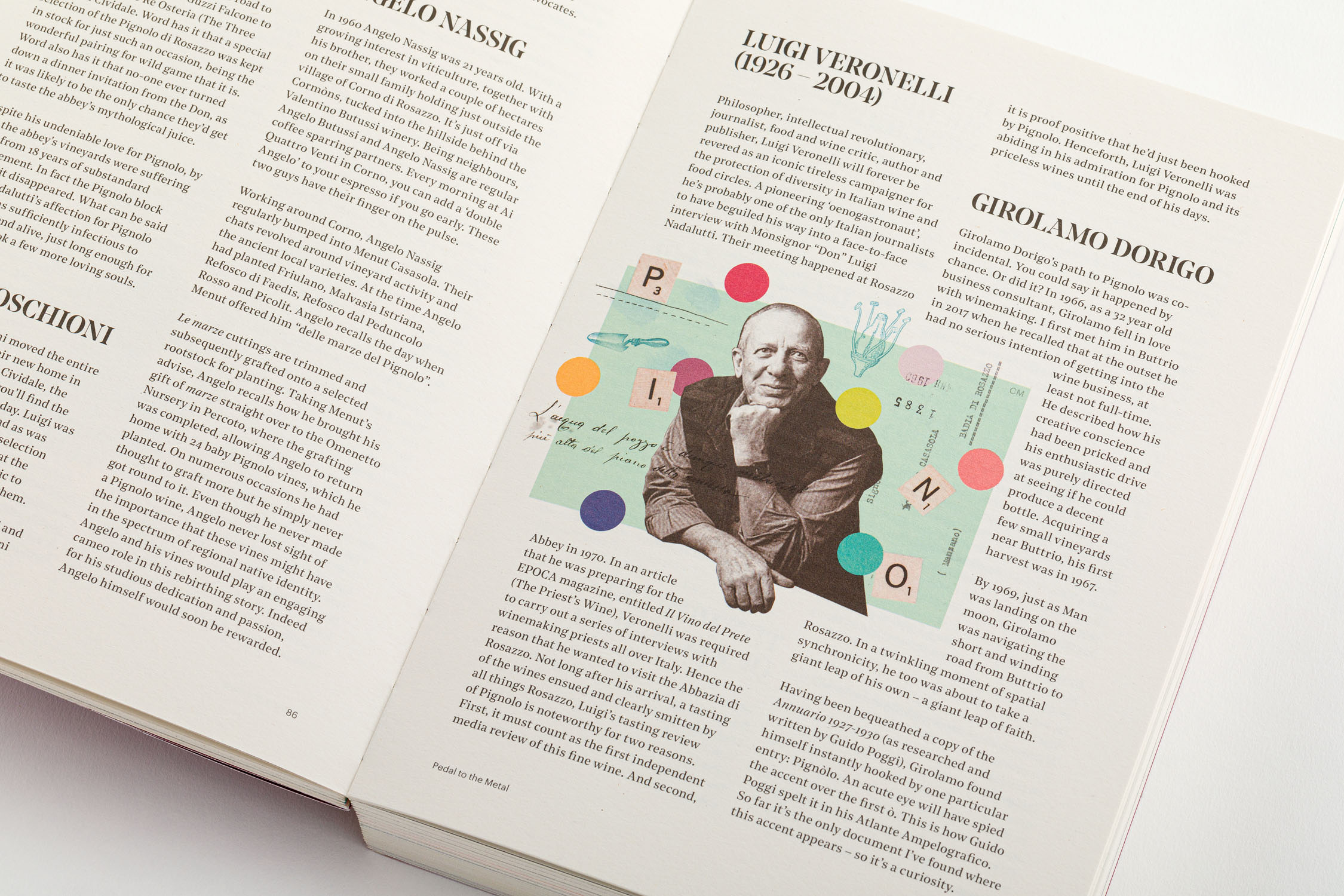

Layers of knowledge, dense facts and a compelling story are punctuated by Dali-esque, collage-like images that at first glance appear to make no sense. Looking at them more closely, I see there is meaning and purpose in every dot and line. Beautiful original artwork (by, it seems, both Ben Little himself and Carin Marzaro) sketch mind maps, cobwebs of connection, pyramids, maps, scribbles and doodles that turn questions and blank spaces into possibilities and poetry.

It’s a book that I almost wondered if I needed to read while standing on my head. Almost certainly not a book to read without a glass of wine in your hand, and it’s not a book for those who prefer information delivered in a spreadsheet. But it’s really important to emphasise that it’s not all Nietzsche and metaphysics. Facts and figures may not be delivered in the didactic style of your average wine book, but Little does give them to us by the bucketload. He may be stargazing and soul-searching, but the book is neither navel-gazing nor self-indulgent. It has the structural rigour of academia. There is a discipline within (and without) the rambling runes. He is, after all, an economist.

So, for those who define substance as information, there is history – of the region, the variety, its name (maybe not the pigna/pine-cone assumption that has long been held to be true), the people. But in Little fashion, the history is entwined with quotes from Descartes and you’ll find yourself on a Stephenson Rocket steam-train from Liverpool to Manchester and then sipping cocktails in New York City. Even his explanation of phylloxera incorporates existential questions.

Interwoven with the history of Pignolo are the cultural aspects that have impacted the grape’s story. ‘Perched along a physical and emotional fault line, Friuli Venezia Giulia is a land of seismic cultural fusion.’ The wounds of war, identity, the impact of economics on the ways people lived and farmed, how silkworms, slopes and politics have shaped the viticultural landscape – all this, Little explores in his strangely off-beat lyrical way.

His research reveals that despite its ignominious demise, Pignolo was once vitally important to the region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia. It has a long history that can be traced by written record back to at least the 14th century, and it’s interesting to read that when rent payments were made (in wine) in the 15th century, there were three recorded types of wine: white wine, red wine and Pignolo wine. Yet by 1970 it had been officially excluded from DOC production. Were it not for Menut (aka Domenico Casasola, born 1910, son of the caretaker of the abbey of Rosazzo), who planted 100 Pignolo vines, most of which are still alive today, the Pignolo renaissance might never have happened.

The next pages are a roll call of names of the men and women who had a hand in saving this grape variety. Their stories, as is always the case in situations like this, are of vision, courage, stubborn determination, defiance and not a little craziness. Little tells them well. (Perhaps, I wonder, because there is an echo of himself in each one.) Particularly moving is the account of Giannola Nonino’s fierce campaign to save the Friulian varieties that had been written out of Friuli DOC legislation. She announced a bando di concorso (competition) in the local newspaper in 1975, offering one million lira to any winegrower who was saving the ancient vines of the region and half a million lira to a journalist who was doing the same. The department of agriculture threatened aggressive legal action against her and the winegrowers. She invited them to be judges of the competition. European law was rewritten. Nonino had taken the first step to save Pignolo.

Do you want to know the polyphenol profile of Pignolo skin in terms of the index of total polyphenols at maturity in mg/kg of grapes? Do you want the index of anthocyanins at maturity, Malvidin-3-O-glucoside*Cl in mg/kg of grapes, or the levels of quercetin, myricetin, kaempferol or the flavan-3-ols that are found in the Pignolo seeds? It’s all there. The shape of the leaves, the five pigments of red and how colour behaves with pH; the IGP and DOC regulations; pruning and training systems; weather patterns and the ages of the soils. Little goes into phenomenal detail about how Pignolo is made, what it tastes and feels like, how it ages and changes at every age.

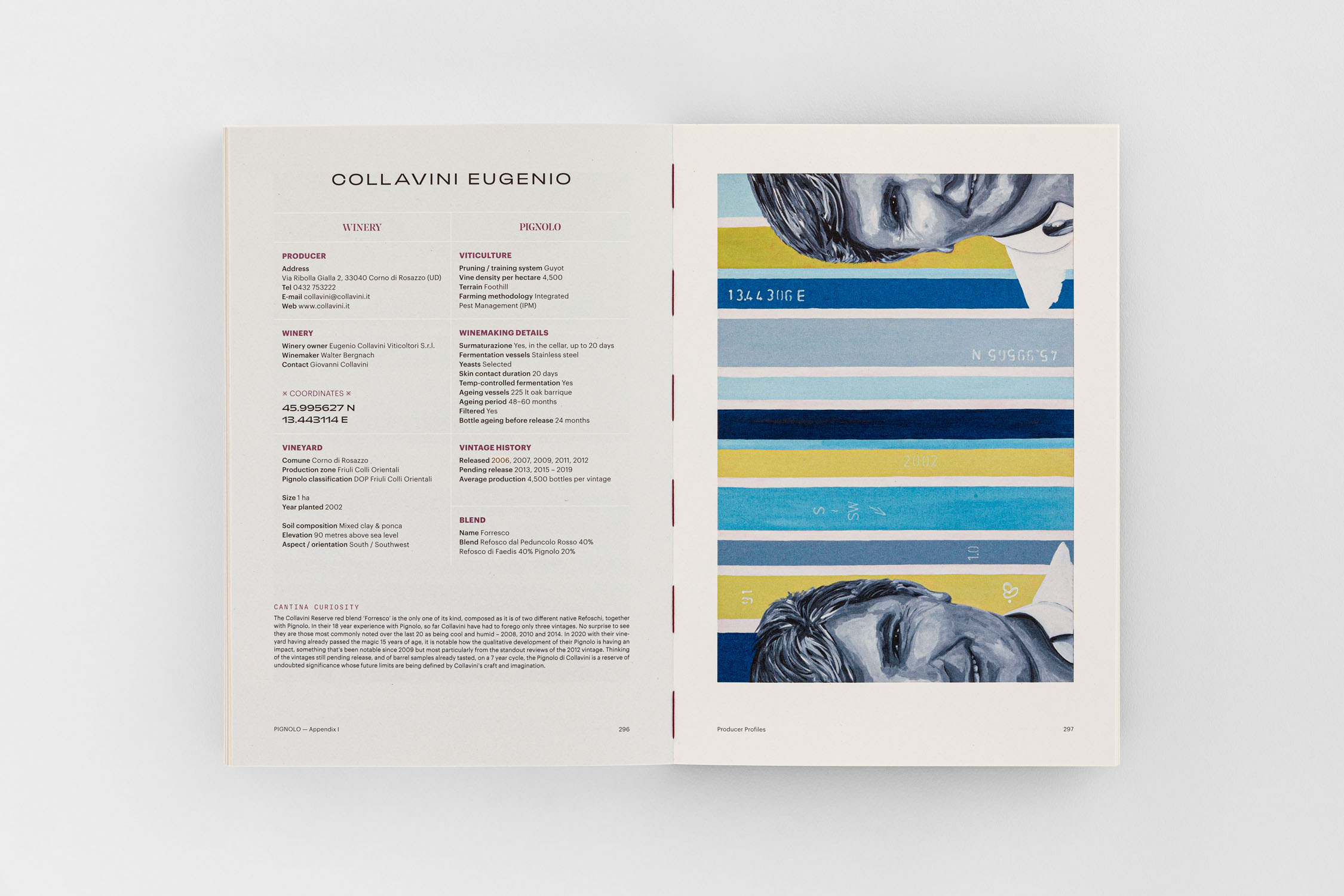

There are timelines and producer profiles (66 of them, each with the most beautiful portraits of the people, each one with the perfect level of detail for a one-page summary) and appendices on plantings, local and abroad. You might not want to know about philosopher Theodor Lipps’ theoretical process of einsehen (‘in-seeing’) but if you can ignore that, this book is loaded with enough data to make any MW deliriously happy.

‘My whole reason, the reason for this book, the reason for The Native Grapes, is first to nurture understanding so that appreciation can grow’. He describes Pignolo as the protagonist in his story, but not an egoist – a humble metaphor for a universal story: regaining what’s lost, rebuilding anew, identity, community, turning siloed knowledge and data into something deeper, recognising the inextricable connections that mean not just survival but thriving. He called it a multi-story and, having read the book, that resonated with me.

The book has two layers running in parallel. On one level, it’s a brilliantly well organised, forensically detailed, orderly and meticulous work of research. Everything you could want to know about a grape variety and its region. On the other, it’s a glorious, rambling madness.

But, as Nietzsche points out, the lines between madness, reason and love are not clear-cut. Little writes, ‘There is always a choice to be made. Love or money?’ and then goes on to say: ‘In fact, as much as anything, you’ll find Pignolo is about tapping into your own universal sense of being, the freedom to be. Pignolo is that and so much more. Pignolo is love painted in broad brush letters on every cellar door … Pignolo people chose love … Yeah, this is a love story.’

And I might have fallen in love.

I think that sums it up.

Tamlyn Currin

JancisRobinson.com

Published on 30.11.2021

Tamlyn Currin / JancisRobinson.com Pignolo Review